Pithecopus rusticus, (Bruschi et al. 2014) (Bruschi, 2014)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2024.2314336 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10818750 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03DD832F-CA2D-FFF0-FF59-B5D867C6FB1D |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Pithecopus rusticus |

| status |

|

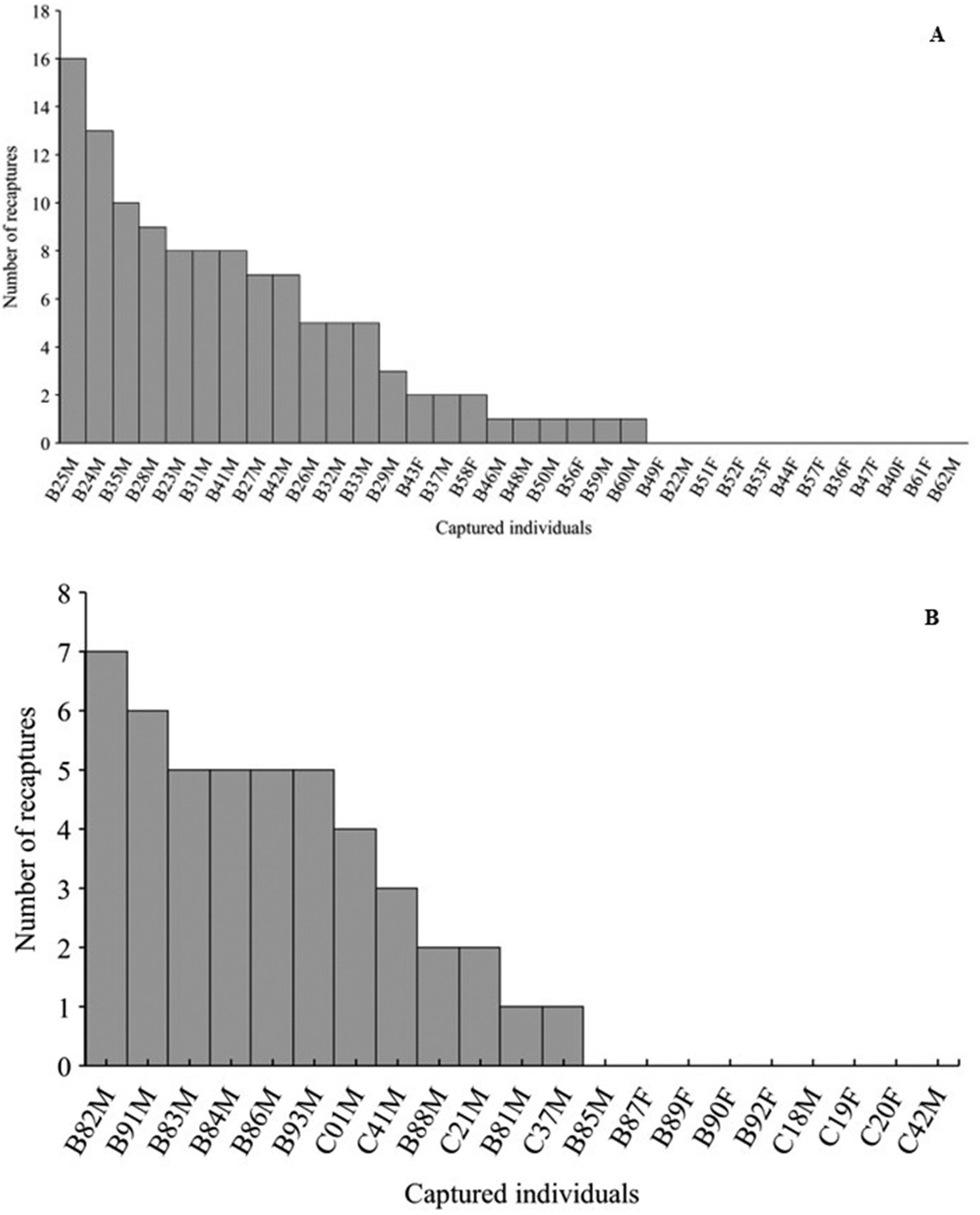

We recorded a total of 91 adult individual of P. rusticus , 69 males and 22 females ( Table 1 View Table 1 ). In the 2015/16 breeding season, we recorded 34 individuals, with a recapture rate of 61% (n = 21 individuals); of these, 34.7% (n = 12) were recaptured more than five times in the sampling period ( Figure 2 View Figure 2 (A)). The Schumacher method estimated a total of 28.9 individuals (25.4–33.8) for this breeding season. In the 2017/18 breeding season, we recorded 21 individuals, with a recapture rate of 57% (n = 12 individuals), and of these, 28.5% (n = 6) were recaptured more than five times in the sampling period ( Figure 2 View Figure 2 (B)). Some males were recaptured in the following days during the same effort (month) and in subsequent months and always in the same location. The Schumacher method estimated a total of 21.0 individuals (19.2–23.2) for this breeding season. Individuals captured on the pond were never recaptured in the marsh 100 m away and vice versa. Most recaptures occurred within the same breeding season. In the 2018/19 and 2020/21 breeding seasons, we recorded 13 and 23 individuals, respectively. However, in November 2018, we recaptured two individuals that were tagged during at the previous breeding season ( October 2017).

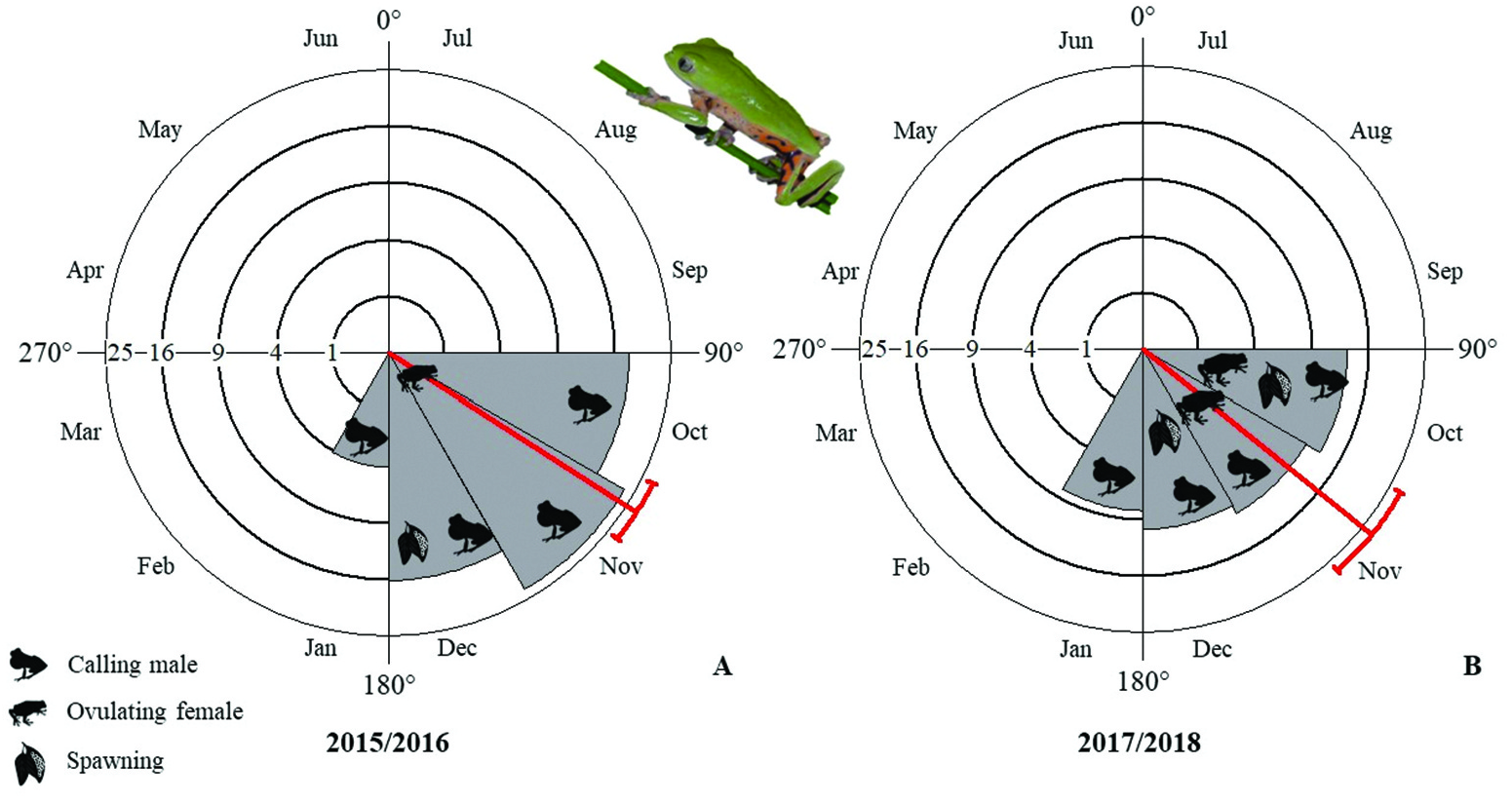

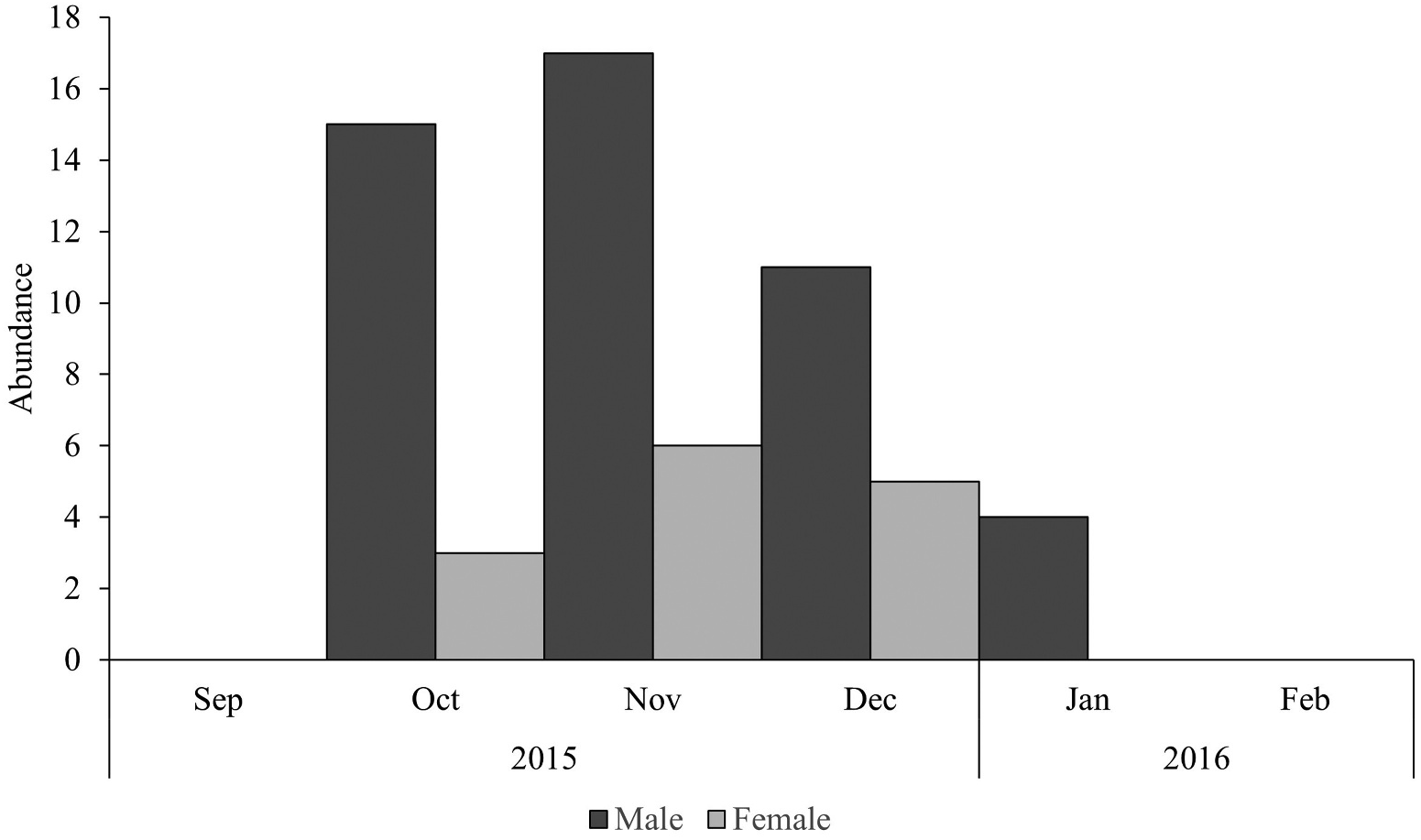

Pithecopus rusticus showed a pattern of seasonal activity ( p <.001 according to Rayleigh’s test), with a peak mean abundance in November ( Figure 3 View Figure 3 ). The degree of seasonality (r) was high for both breeding seasons 2015/16 and 2017/18 (r = 0.90 and r = 0.85, respectively). Males called from October to January, with greater activity at the beginning of the period ( Figure 4 View Figure 4 ). Variation in abundance of P. rusticus among the sampled nights was significantly related with RH (R 2 = 0.58; adjusted R 2 = 0.26; F (4,35) = 4.49; p <.01 and β = 0.57; p <.01). There was no significant influence of rainfall (β = −0.19; p =.24), minimum temperature (β = 0.13; p =.40) or maximum temperature (β = −0.11; p =.64) on the abundance of individuals.

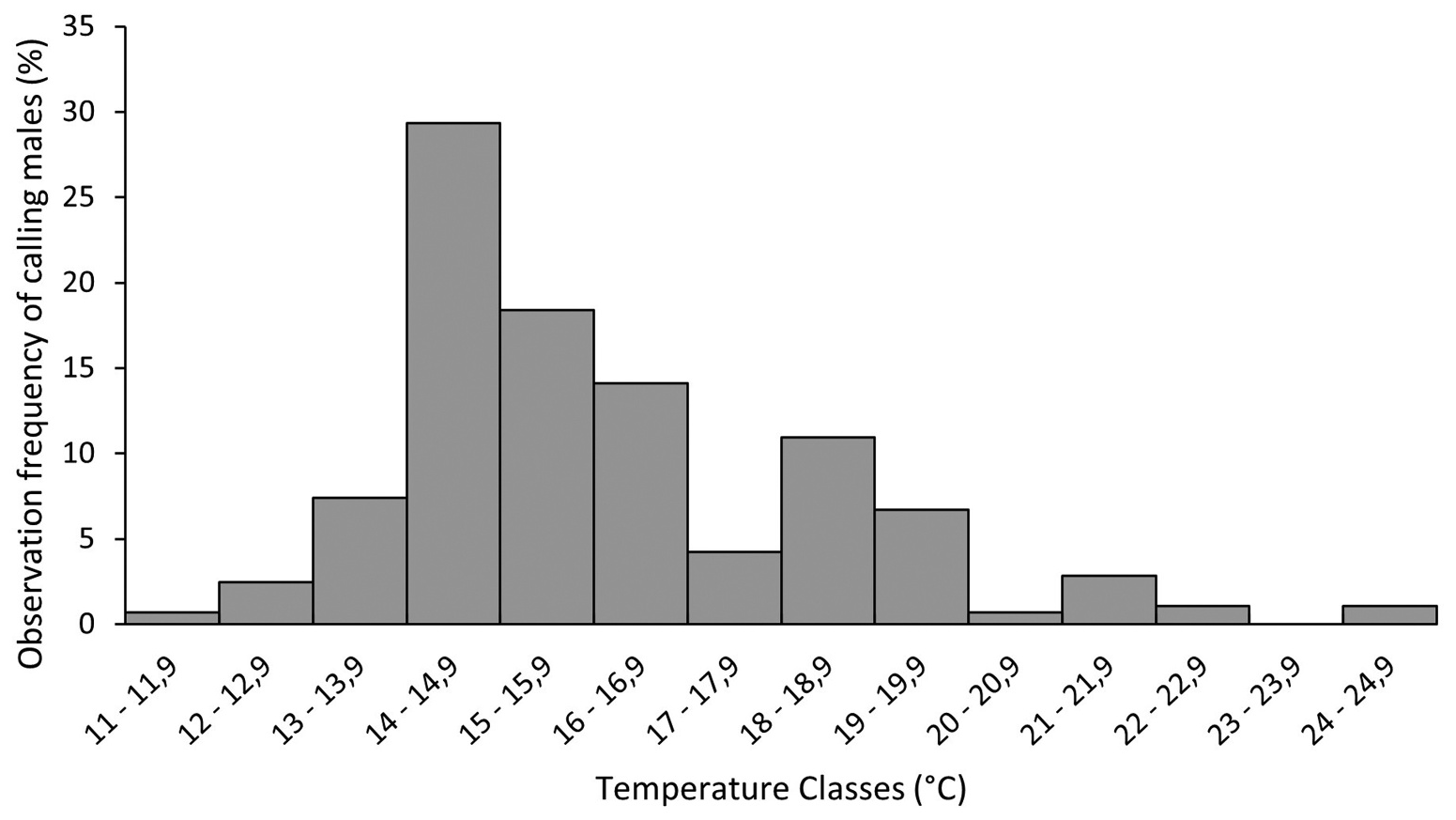

Calling activity also varied throughout the night (F( 2,66) = 28.57; p <.01), since a lower frequency of males called at the beginning of the nocturnal sampling (7pm) than in the middle (9pm) or at the end of this period (11pm) (Tukey p <.01 for both comparisons). The frequency of calling males did not varied between the middle (9pm) and the end of the nocturnal sampling period (Tukey p <.01). In addition, the highest frequency of calling males was observed at temperatures between 14 and 16.9°C (61.8%; n = 175), with a peak of activity between 14.0 and 14.9°C (29.3%; n = 83) ( Figure 5 View Figure 5 ). The majority of calling males used mainly leaves of Fimbristylis ( Cyperaceae ;>50%) and Juncus ( Juncaceae ; ~20%) from the edges of ponds and marsh ( Table 2 View Table 2 ). However, males also used leaves of Senecio ( Asteraceae ) and Eriocaulon ( Eriocaulaceae ) as calling sites (<30%). Calling males perched at heights of 16.00 ± 10.09 cm ( 1–33 cm; n = 17) and at distances of 155.50 ± 393.02 cm ( 5– 1400 cm; n = 12) from the edges to the centre of the pond. Non-calling males showed the same pattern in vegetation use and were perched at heights of 18.50 ± 9.89 cm ( 10– 30 cm; n = 4; Table 2 View Table 2 ). The distance from the edges to the centre of the pond was 6 ± 4.24 cm ( 3–9 cm; n = 2).

Females also used mainly leaves of Fimbristylis (>50%) and Juncus (about 15%) at the edge of pond and marsh, perched at 24.80 ± 17.20 cm ( 0–54 cm; n = 13) high. Likewise, in a smaller proportion (>20%), they used leaves of Senecio ( Asteraceae ) and Eriocaulon ( Eriocaulaceae ). Most of the females’ perches were established at 173.70 ± 433.00 cm ( 2– 1400 cm; n = 10) from the edges to the centre of the pond, and few (n = 2) were found outside the edges at 7.00 ± 9.90 cm ( 0–14 cm; n = 2). Recaptured males and females showed the same pattern of microhabitat use as in the first captures ( Table 2 View Table 2 ).

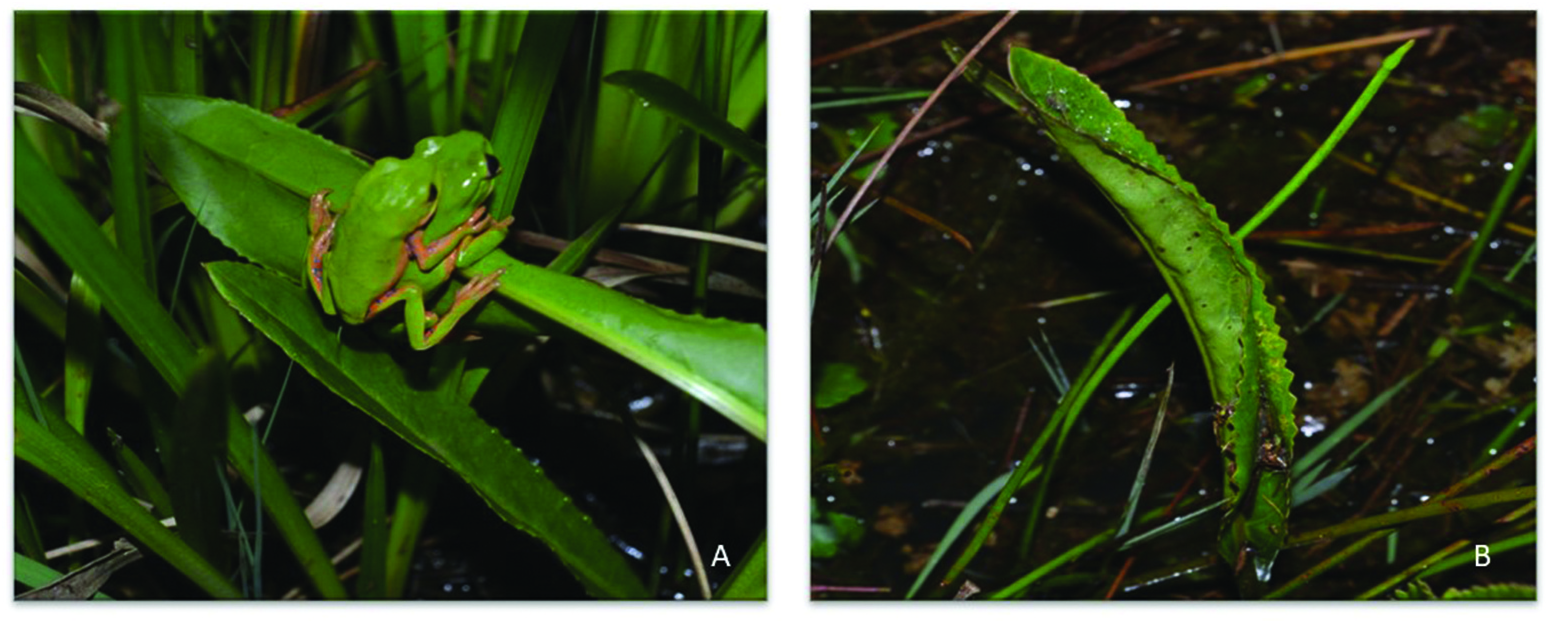

Females were larger and heavier than males ( Table 3 View Table 3 ; Figure 6 View Figure 6 (A)). The OSR was male-skewed, with 0.27 (± 0.22, 0–0.50, n = 4) females to each male in the 2015/16 breeding season and 0.17 (± 0.21, 0–0.44, n = 4) females in the 2017/18 breeding season. We observed spawning in December 2015 (n = 16), October 2017 (n = 6), October and December 2020 (n = 2 and n = 7, respectively) and January 2021 (n = 1) ( Figure 6 View Figure 6 (B)). The spawning consisted of yellowish eggs, surrounded by gelatinous capsules. The spawns contained a mean of 43.00 ± 5.28 eggs (26–46; n = 13), with a diameter of 3.26 ± 0.45 mm ( 2.88–4.19 mm; n = 13). Most of the spawns were found on leaves of Senecio (n = 26) and some on leaves of Eriocaulon (n = 5). Pithecopus rusticus used only one folded leaf for each egg-laying ( Figure 6 View Figure 6 (B); Table 4 View Table 4 ). The spawns were hanging over the water (88%; n = 14) or on the water’s edge (13%; n = 2). The mean distance from spawns to the edge was 19.00 ± 22.18 cm ( 1–2500 cm; n = 10) for those located internally to the edge and 17.00 ± 16.45 cm ( 2–50 cm; n = 6) for those located externally. The spawns were at a height of 23.50 ± 6.41 cm ( 15–36 cm; n = 16) above the water surface (81.25%; n = 13) or wet ground (18.75%; n = 3).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Phyllomedusinae |

|

Genus |